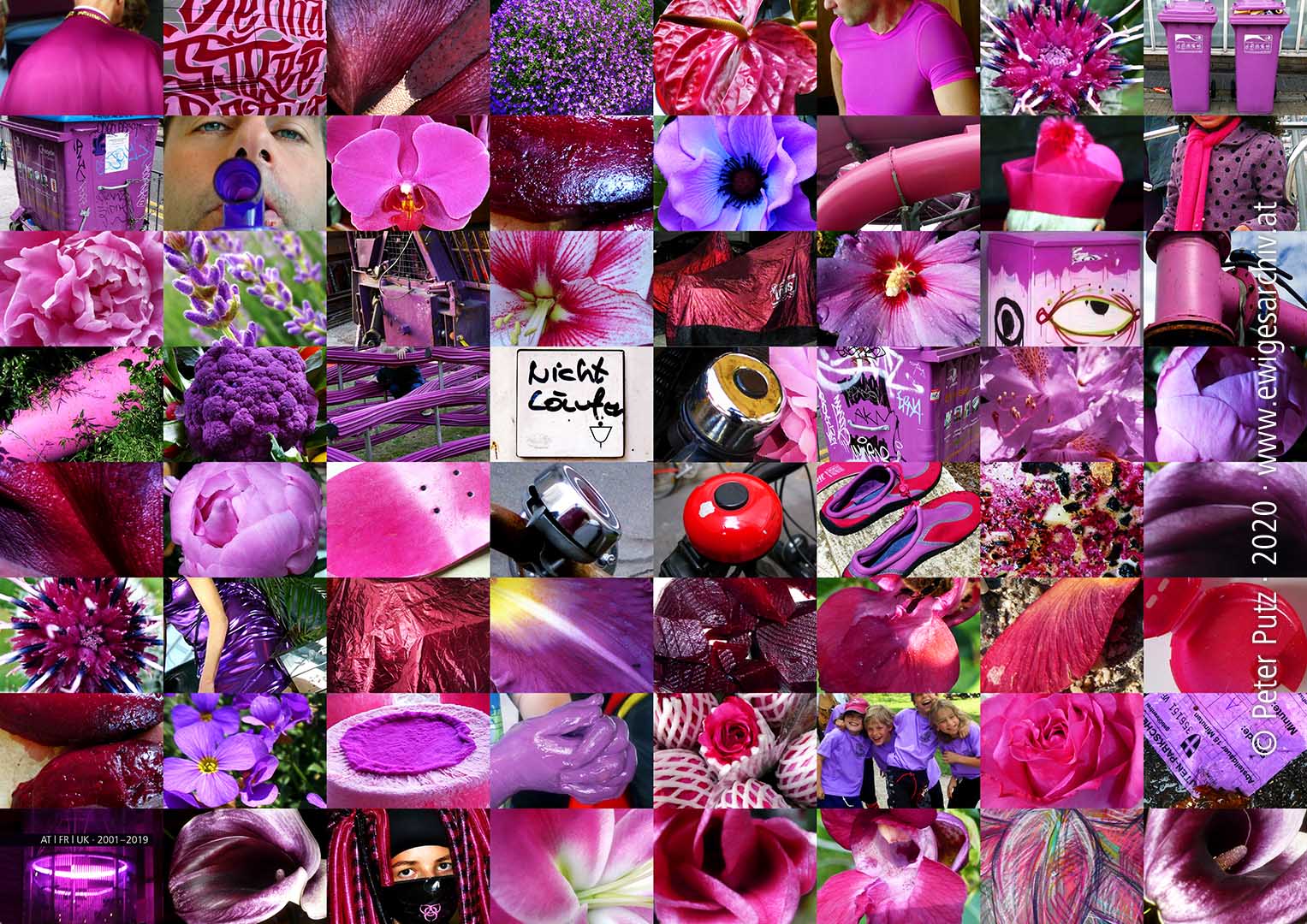

Karfreitag: die Glocken hängen still am Turm, bitte nicht läuten und klingeln! Und: Ein kurzer Schlenkerer zum Karfreitagsabkommen in Nordirland. Splendid Isolation_29. AT | FR | UK · 2001–2019 (© PP · Ewiges Archiv) „Der Karfreitag (althochdeutsch kara ‚Klage‘, ‚Kummer‘, ‚Trauer‘) ist der Freitag vor Ostern. Er folgt auf den Gründonnerstag und geht dem Karsamstag voraus. Christen gedenken an diesem Tag des Leidens und Sterbens Jesu Christi am Kreuz.“ (wiki) Die liturgischen Farben sind violett, schwarz und rot. Ich war ein begeisterter „Ratscherbua“ und bin mit anderen Buben (damals: nur Buben! Heute Buben und Mädchen) einige Jahre lang am Karfreitag und Karsamstag in Langwies ab 5 Uhr losgezogen. Mehrmals am Tag sind wir eine bestimmte Strecke von Haus zu Haus gegangen, haben vor dem jeweiligen Haus einige Kreise gedreht, geratscht und kurze Sprüche aufgesagt. Am Karfreitag diesen: „Die Glocken hängen still am Turm, bedenk’ Du stolzer Erdenwurm, dass Deine Zung’ einst ruhig ist, drum hochgelobt sei Jesu Christ!“ Die Glocken waren ja nach Rom geflogen, die Ratscher ersetzen sie mit ihren Trommel- oder Fahnl-Ratschen. Erste Raucherlebnisse: Am Vortag hatte einer von uns im Einzimmer-Geschäft bei Herrn Promberger „Tschick“ gekauft („Für den Vater!“) – „Arktis“ oder „Nil“ Menthol-Zigaretten – die wir dann auf dem Soleweg geraucht haben. Wenn wir keine Zigaretten hatten, dann wurden Lianen angezündet und „geraucht“. Unvergessen, bin ganz gerührt, während ich das schreibe.

Das Karfreitagsabkommen (englisch Good Friday Agreement, Belfast Agreement oder Stormont Agreement, irisch Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta) ist ein Übereinkommen zwischen der Regierung der Republik Irland, der Regierung des Vereinigten Königreichs und den Parteien in Nordirland vom 10. April 1998. Mit dem Karfreitagsabkommen wurde die seit den 1960ern gewaltgeladene Phase des Nordirlandkonflikts beendet und in eine politische Konsenssuche überführt. (wiki)

Der Karfreitag wird auch stiller Freitag oder hoher Freitag genannt. In der katholischen Kirche ist der Karfreitag ein strikter Fast- und Abstinenztag. Er ist Teil der österlichen Dreitagefeier (Triduum Sacrum oder Triduum Paschale), die mit der Messe vom letzten Abendmahl am Gründonnerstag beginnt, sich über den Karfreitag und den Karsamstag, den Tag der Grabesruhe des Herrn, erstreckt und mit der Feier der Auferstehung Christi in der Osternacht endet.

Diese österliche Dreitagefeier stellt in allen Konfessionen das älteste und höchste Fest des Kirchenjahres dar und wird als das Pascha-Mysterium liturgisch wie ein einziger Gottesdienst gefeiert, der am Gründonnerstag mit der Eröffnung des Gottesdienstes beginnt und in den Segen am Ostermorgen mündet.

Das Karfreitagsabkommen (englisch Good Friday Agreement, Belfast Agreement oder Stormont Agreement, irisch Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta) ist ein Übereinkommen zwischen der Regierung der Republik Irland, der Regierung des Vereinigten Königreichs und den Parteien in Nordirland vom 10. April 1998. Mit dem Karfreitagsabkommen wurde die seit den 1960ern gewaltgeladene Phase des Nordirlandkonflikts beendet und in eine politische Konsenssuche überführt. Ziel war es, einen modus vivendi zum Nutzen der Bevölkerung Irlands zu finden. Zwar gab es nach dem Karfreitagsabkommen noch einzelne Gewalttaten, diese hatten aber keinen Rückhalt mehr in der Bevölkerung und eskalierten nicht mehr.

Der Nordirlandkonflikt (englisch The Troubles, irisch Na Trioblóidí) beherrschte die nordirische Politik der Jahre 1969 bis 1998. Es handelt sich bei dem Konflikt um einen bürgerkriegsartigen Identitäts- und Machtkampf zwischen zwei Bevölkerungsgruppen in der nach der Unabhängigkeit der Republik Irland (als Irischer Freistaat) 1920/22 britisch gebliebenen Provinz Nordirland, also den englisch- und schottischstämmigen, unionistischen Protestanten und den überwiegend irisch-nationalistischen[1] Katholiken. Radikale Vertreter des Unionismus werden auch als Loyalisten und radikale Nationalisten auch als Republikaner bezeichnet. Das hervorstechendste Merkmal Nordirlands ist die Segregation der Bevölkerung in zwei große Gruppen, je nach Ethnie und Konfession. Diese Trennung spiegelt sich sogar in der Siedlungsgeographie: Allgemein gesprochen sind die nordöstlichen Gebiete (vor allem das Umland und Teile Belfasts und die Küste von County Antrim) heute protestantisch und die westlichen (um County Derry und County Tyrone) katholisch dominiert. Der Nordosten ist sehr viel stärker industrialisiert als der ländliche Westen. Fast alle größeren Städte sind protestantische Hochburgen (bis auf Derry und Newry). Auch Belfast, das mit Abstand größte Ballungszentrum, zählt dazu. Diese größeren Städte wiederum sind häufig in protestantische und katholische Wohnviertel (z. B. in Belfast Falls Road (katholisch-irisch) und The Shankill (protestantisch-britisch)) segregiert.

Good Friday: the bells hang silently on the tower, please do not ring and ring the bell! And: A short dangle to the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland. Splendid Isolation_29. AT | FR | UK · 2001–2019 (© PP · Ewiges Archiv) “Good Friday (Old High German kara ‘complaint’, ‘grief’, ‘grief’) is the Friday before Easter. It follows Maundy Thursday and precedes Holy Saturday. Christians commemorate this day of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ on the cross. ”(Wiki) The liturgical colors are violet, black and red. I was an enthusiastic “Ratscherbua” and went out with other boys (then: only boys! Today boys and girls) for a few years on Good Friday and Holy Saturday in Langwies from 5 a.m. Several times a day we walked a certain distance from house to house, turned a few circles in front of the respective house, rattled and said short words. On Good Friday this: “The bells hang silently on the tower, consider ‘you proud earthworm that your tongue is once quiet, so be praised to Jesus Christ!” The bells had flown to Rome, the ratchets replace them with their drum or Fahnl ratchets. First smoking experiences: The day before, one of us had bought “Tschick” from Mr. Promberger in the one-room shop (“For the father!”) – “Arctic” or “Nil” menthol cigarettes – which we then smoked on the brine path. If we didn’t have cigarettes, lianas were lit and “smoked”. Unforgettable, I am touched as I write this.

The Good Friday Agreement (Belfast Agreement or Stormont Agreement, Irish Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta) is an agreement between the Government of the Republic of Ireland, the Government of the United Kingdom and the parties in Northern Ireland of April 10, 1998. The Good Friday Agreement ended the violent phase of the Northern Ireland conflict since the 1960s and turned it into a political search for consensus. (wiki)

Good Friday is also called silent Friday or high Friday. Good Friday is a strict day of fasting and abstinence in the Catholic Church. It is part of the Easter three-day celebration (Triduum Sacrum or Triduum Paschale), which begins with the Mass from the last supper on Maundy Thursday, extends over Good Friday and Holy Saturday, the day of the rest of the Lord’s tomb, and with the celebration of Christ’s resurrection in the Easter night ends.

This Easter three-day celebration is the oldest and highest festival of the church year in all denominations and is liturgically celebrated as the Paschal Mystery like a single service that begins on Holy Thursday with the opening of the service and ends in the blessing on Easter morning.

The Good Friday Agreement (Belfast Agreement or Stormont Agreement, Irish Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta) is an agreement between the Government of the Republic of Ireland, the Government of the United Kingdom and the parties in Northern Ireland of April 10, 1998. The Good Friday Agreement ended the violent phase of the Northern Ireland conflict since the 1960s and turned it into a political search for consensus. The aim was to find a modus vivendi for the benefit of the people of Ireland. There were still individual acts of violence after the Good Friday Agreement, but these no longer had any support from the population and no longer escalated.

The Northern Ireland conflict (English The Troubles, Irish Na Trioblóidí) dominated Northern Irish politics from 1969 to 1998. The conflict is a civil war-like identity and power struggle between two population groups in the after the independence of the Republic of Ireland (as the Irish Free State) 1920/22 remained British province of Northern Ireland, so the English and Scottish-born, Unionist Protestants and the predominantly Irish nationalist [1] Catholics. Radical representatives of Unionism are also known as loyalists and radical nationalists as Republicans. The most prominent feature of Northern Ireland is the segregation of the population into two large groups, depending on ethnicity and denomination. This separation is even reflected in the settlement geography: Generally speaking, the northeastern areas (especially the surrounding area and parts of Belfast and the coast of County Antrim) are today Protestant and the western (around County Derry and County Tyrone) Catholic dominated. The northeast is much more industrialized than the rural west. Almost all major cities are Protestant strongholds (except Derry and Newry). Belfast, by far the largest conurbation, is one of them. These larger cities, in turn, are often segregated into Protestant and Catholic residential areas (e.g. Belfast Falls Road (Catholic-Irish) and The Shankill (Protestant-British)).